|

|

|

|

Courtesy BBC report By Richard Black A new space-based study of Antarctica shows its ice sheet is shrinking. Researchers used satellites to plot changes in the Earth's gravity in the Antarctic during the period 2002-2005. Writing in the journal Science, they conclude that the continent is losing 152 cubic km of ice each year, with most loss in the west.

David Vaughan, British Antarctic Survey

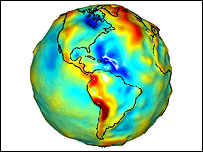

In recent years scientists have found other evidence that West Antarctic ice is melting, which could contribute to sea level rise. In his contribution to a recent report on climate change, the director of the British Antarctic Survey, Chris Rapley, described the West Antarctic ice sheet as "a giant awakened". But gathering comprehensive data on both the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets has not been straightforward, and studies have produced apparently contradictory results, with some indicating a loss of ice and others that sheets are thickening. Favours from Grace The new study, conducted by scientists at the University of Colorado at Boulder, uses a technique which has not been tried before: measuring gravity over Antarctica. Data comes from a pair of satellites together known as Grace which orbit the Earth in tandem, measuring changes in its gravitational field. When they fly over regions where there is lots of material below, such as mountain ranges, or where crustal rocks are more dense, they will register an increase in the Earth's gravity - tiny, but measurable.

"We see the entire ice sheet and measure the mass change of the entire ice sheet; then we look at the east and west separately," she told the BBC News website. Overall, Dr Velicogna's group found an annual decrease in ice sheet mass of 152 cubic km. There is a clear loss in the west, whereas the mass of the East Antarctic sheet appears to be constant. This loss of ice equates to an annual rise in the global average sea level of 0.4mm; by contrast, the rise from thermal expansion of seawater is estimated at about 1.8mm per year. Exciting times "This is a completely new way of measuring the ice sheet mass balance, and so it's extremely exciting," commented David Vaughan of the British Antarctic Survey, a specialist on the issue. "It has advantages and disadvantages. The advantage is that you can see entire ice sheets; but it will never manage to pinpoint where changes are happening." Previous studies have mainly relied on data from radar altimeters on board satellites, which cannot measure on steep slopes; and from laser altimeters on aircraft, which do not give comprehensive coverage. Last year an altimeter study indicated that parts of the East Antarctic ice sheet were getting thicker, by about 1.8cm per year. "What they asessed was what's changing in the interior, and they found it's growing; but that's not in contrast with what we found," said Isabella Velicogna. "With increasing temperatures you get increased precipitation, so what may happen is that ice in the interior grows and then at the coast you have mass loss. "So what we found is that for the continent as a whole, the balance between the two is negative." Extending mission

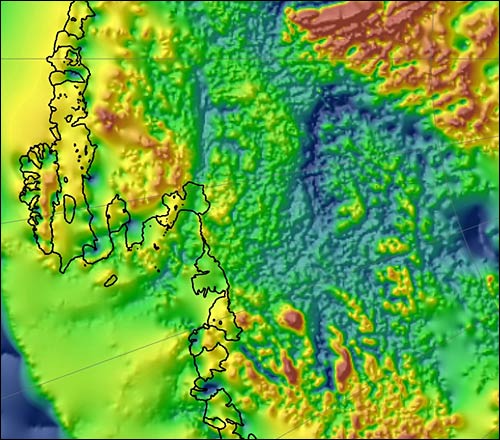

This should increase the accuracy of their data. But there is another issue which needs resolving. Grace is unable to discriminate between ice and rock. And the rock surface of Antarctica, below the ice sheet, is rising. The new research paper attempts to correct for this by estimating the rate of rise through computer models of the Earth's interior. But uncertainties in the models produce uncertainties in the team's estimates of changes to the ice: the annual loss could be as low as 72 cubic km, or as high as 232 cubic km. Much better, said David Vaughan, would be to measure the rise directly, and eliminate the uncertainties. "The best way would be to go to rock outcrops on Antarctica, put GPS receivers on them and measure how rapidly they're rising," he told the BBC News website. "That is done at the moment in a few places, but not in enough, and a new programme is being planned." The British Antarctic Survey is also looking to harden up indications that rising sea temperatures are lubricating the bottom of the West Antarctic ice sheet, causing it to move faster towards the sea - a mechanism which also appears to be affecting the Greenland ice. Complete melting of either the West Antarctic or Greenland sheets would raise global sea levels by about seven metres, probably on a timescale of centuries. Comment by Dr Sherwood: Ok lets examine this. If the report states that the ice sheet is losing 152 cubic km of ice each year, with most loss in the west. And the rock ridges are rising then it would be logical to assume that the loss is actually greater if the density gravity wise is rising. Ice mass has the same effect on gravity as rock in that the density is affected by minerals in the rock and elements from gases to small mineral particals as well as the water itself. A somple test can be done to show this by taking a small bar magnet and place a block ofice over a magnetic object such as another bar magnet. Measure the distance before the repelling force is felt then do the same with a rock. Then use a smaller piece of ice and measure the difference before resistance is felt. The variation is caused by thermal internal dynamics which affect gravity waves in any number of ways but one way is to distort the travel. So after all of that there is a strong chance that the antarctic is losing ice.. So why more at the west? And where exactly is west Antarctic? Here! Here is a thought what if the land mass is rising faster there than anywhere else on the frozen continent. In the map below we are looking at a image of the ocean floor beneath the ice, and who did it and where is it of..British and US scientists have produced a remarkable map of the underside of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS).

Dark blue denotes low areas and red marks the highest points. It can be seen that some of the interior is as low (3km below sea level) as the ocean floor off the continental shelf in the bottom left-hand corner of the image. (Image: BBas/Agasea) If all the surveyed zone were to melt, it would produce a global ocean rise of 1.3m.

Can you see the glacial mouth and where the flow is coming from! It shows in unprecedented detail the mountains, troughs and lakes that lie under the great ice mass.

|

|

(c) Copyright 1993-2008 Publishing |

| [Home] [Main index] [Environment] [Antarctica] [Ice loss] |

This is a completely new way of measuring the ice sheet mass balance, and so it's extremely exciting

This is a completely new way of measuring the ice sheet mass balance, and so it's extremely exciting